27.7.03

It’s a certain textural beauty Malick goes for, and he well achieves it. Shot after shot fills the screen with ravishing framing, shape, and light; this is vividly expressionistic cinema, mood cinema, and if you’re in the right state of mind, it can be extremely gratifying. It’s a good one for a Sunday morning.

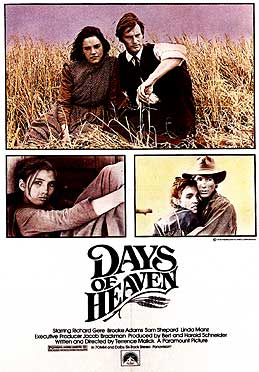

The film basically tells the story of impoverished American migrant workers directly before World War II; the three we see, comprised of Richard Gere, Brooke Adams (his lover, posing as his sister) and the child, receive the mixed blessing of being taken in by a wealthy landowner (Sam Shepard) they’ve been working for. This is due solely to his infatuation with Adams, which of course means a love triangle, but this story is almost background to the vast canvas Malick presents to us. This is definitely not the last time I’ll be watching this one.

Interesting trivia: Linda Manz, who plays the child narrator/protagonist, also appeared, about 20 years later, in Harmony Korine's Gummo as a homicidal (or is she just "playing"?), tap-dancing suburban mom who lost her husband in a devastating tornado.

Running with Scissors was a breezy trip, despite the very uncomfortable events it recounts. Burroughs plays nearly everything for laughs (it’s much less successful in the rare instance he lets too much pathos creep in). His highly unusual and extremely funny childhood and adolescence are fantastic examples of the pros and cons of a liberated, unstructured postmodern approach to child-rearing (when his already fairly mental parents divorced, he was raised for the most part by his mother’s psychologist and his highly unconventional family). His book gets shelved next to David Sedaris’s as far as the gayness goes; they have enough perspective and honesty to be much more (and much more worthwhile) than “my traumatic gay life” stories. Gay people can be interesting, these books imply, but not merely by dint of their orientation. Which is, as I myself have believed for most of my own gay life, exactly right.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]