27.5.04

"SEX IS COMEDY

and

ANATOMY OF HELL"

My second helping of the Seattle International Film Festival consisted of a double feature by Catherine Breillat at Capitol Hill’s Egyptian Theater, which is usually home to all sorts of interesting second runs and revivals and, as a bonus, offers a unique “Egyptian” decor. As a minus- especially when you consider the torrential weather of yesterday evening- there’s scant waiting room inside the lobby, and the space was reserved for those snooty Gold Pass holders (not for mere ticket holders like myself, the ugly stepchildren of film festivaling).

The only other Breillat film I’ve seen was Fat Girl, which I made a point of attending during one of my excursions to New York once I realized it was playing there (I believe it found its way to Portland for a very brief run months later, which gives you some perspective on the status bestowed by indie-film distributors upon our little out-of-the-way cities that aren’t New York or Los Angeles). The story of a petulant, morose, and, yes, fat young girl, her tortured older sister, and her discontented parents, especially her mother (played by Atom Egoyan regular Arsinee Khanjian) and their insular bourgeois villa life. The film is marked by the violence, sexual chaos, and despair underlying their existence (and which one couldn’t be blamed for assuming Breillat feels underlies life in general), and only the misfit young girl seems capable of really grasping and eventually, narrowly escaping it. It was bracing, accomplished, and a little horrifying in that ultramodern-understated way that the French seem so fond and capable of.

The first of last night’s Breillat double-dip was Sex is Comedy, which evidently is the slightly fictionalized autobiography of Fat Girl’s production. There is the Breillat-like director, a frantic perfectionist who’s written a screenplay involving some very uncomfortable, very graphic, and very long sex scenes, which she then has to convince her alternately moody, spoiled, and just eccentric actors (who seem to detest her almost as much as they detest each other) to perform in a manner that she’s choreographed precisely from second to second.

The film does, in fact, succeed as a comedy, but the humor is derived not so much from the sex as from the constantly escalating anxiety and conflict surrounding the performance of fictional sex for a director, crew, and camera. Watching it, you can hardly imagine these people behaving any differently, given the rather singular creative experience they’ve put themselves in for; when they finally get the scene right, and we see it in all its real-time emotional and physical brutality, it’s an emotional moment similar to that following a live birth.

Sex is Comedy would’ve made an excellent double feature with Fat Girl, but thank god there was some sort of levity preceding Anatomy of Hell. Using the word “anatomy” in the title is the only thing remotely like a joke to be found anywhere near this one; otherwise, it's one of the most precisely, systematically unflinching, problematic films I’ve ever seen.

The story and its chronology are very simple: A very unhappy-looking young woman is hanging out at a gay bar, surrounded by happy hedonists. She’s rudely jostled by a handsome man as she makes her way to the toilet, where she attempts to slash her wrists. The rude man finds her there and takes her to the doctor. She subsequently offers him money in return for coming home with her and looking at her naked body. This is something she knows is not his cup of tea, and the proposition is presented by her as almost a sort of challenge.

After this “prologue” section, the rest of the film is divided evenly into four “chapters,” each comprised of one of the nights spent by this man and this woman at her isolated home by the sea. It becomes apparent that the woman means to both seduce and repel this man, to show him not only her naked body but its every discomfiting function. With an apparent combination of curiosity and obstinacy, the man finds himself doing much, much more than looking. We, as the audience, are also treated to extreme, completely unabashed, and effluvient anatomical close-ups. If you're made uncomfortable by vividly and repeatedly depicted menstruation or graphic talk of sex accompanied by an emphatic, insistent degree of honesty about the other functions of the commonly sexualized orifices (it’s difficult to decide which of them comes to seem less erotic on the movie’s terms), the ones our libidos scurry to make us forget, you may want to think twice before watching this one.

But that’s where the film really works: As a challenge to us to see to what degree our own relatively “normal” sexual responses rely upon blocking out the reality this woman is adamantly impressing upon this man. On this level, the film is a stark, grossly unpleasant exploration of something that does, in fact, ring true.

Where Anatomy of Hell seems to me to fail is in its presumptuous and pedestrian assumptions about what causes the characters to find themselves at their current attitudes and actions. The woman seems to believe the man is gay because he hates women and their softness, “lumpiness,” and blood, and that the homosexual male is the most potent example of masculine insecurity, the most extreme manifestation of all men's fear and loathing of female physicality. Nothing the man says or does- even when he’s having intercourse with the woman- would seem to refute this. In a beautiful but troubling flashback triggered by his first glimpse of her genitalia, he recalls the time he swiped a baby bird from its nest; the way the pink, bloody, featherless bird corpse looked after it had died in his pocket and he’d stepped on it in a childish fit of cruelty is the only thing he can think of as he studies her intimate anatomical revelation.

Far too much of the man and woman’s philosophizing is, frankly, either badly translated or embarrassingly sophomoric- a highfalutin, lavendar-prose parody of itself. But could this be the point? Is Breillat indicting these people for self-destructively wallowing in their own mindless, absolutist, calcified notions of sex and gender and their accompanying self-pity and self-martyrdom? Is she mocking identity politics, drowning easy, Gloria Steinem-style bite-sized sloganeering in a sea of menstrual blood? Is she merely pushing buttons? Is the film so relentless out of genuine aesthetic/ideological concerns, or is the director just overly self-impressed at her own daring? Maybe the most important question the film forces us to arrive at is: Aren’t these buttons that beg to be pushed to the exact degree that we continue, in Western culture, to repress, evade, and gloss them over?

Along the same lines as Sex is Comedy, a true classic of films-about-filmmaking: Truffaut’s Day for Night. Truffaut is a cinematic confectioner, and his sweet, kind, intelligent and engaging way of looking at the world is in full force here. This one is basically a portrait of the dysfunctional family comprising all cast/crew during the shooting of any film. Each character- the legendary older supporting actress, a good-time gal who drinks and can’t remember her lines; the former matinee idol whose gossip-topic romance is with a man (“We thought he’d turn up with a Lolita, and instead he shows up with a handsome Romeo!” the imperturbable script-girl says- and this was 1973, the era of The Boys in the Band!); the lead actress who also turns out to be the film’s guardian angel; the lead actor who’s just a romantic little boy that can’t grow up; and the assorted eccentrics, loafers, and hangers-on surrounding them, including Truffaut himself as the film’s director. Truffaut brings his usual witty mis-en-scene and lively visual style to the story, and there's a sort of cumulative depth to the seemingly breezy proceedings. Day for Night is charming, plain and simple, but its charm is perfectly maintained with just a hint of tender melancholy brought on by Truffaut’s eager love of the cinema.

25.5.04

"YOU'RE A WASTED FACE, YOU'RE A SAD-EYED LIE, YOU'RE A HOLOCAUST"

My varied and surprisingly extensive recent home viewing has included two out-of-the-way Holocaust-themed English-language dramas from famed European directors:

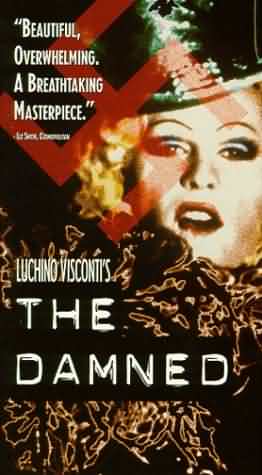

-Luchino Visconti's The Damned. I've never seen a Visconti film before, and it seems doubtful that this is the one to start with (the prime candidate for that being The Leopard, which is very shortly to be released on DVD by Criterion), but his reputation precedes him: It's all visual engorgement, content be damned (pun intended). In "I Can't Get That Monster Out of My Mind," one of her very few essays on the cinema, the notoriously hard-nosed Joan Didion very unfavorably compared Visconti to his countryman Antonioni (who makes "beautiful, intelligent, intricately and subtly built pictures, the power of which lies entirely in their structure"): "Visconti... has less sense of form than anyone now directing. One might as well have viewed a series of stills, in no perceptible order, as his The Leopard."

Now, I consider Didion a first-rate writer, but her relentless, absolutely-no-bullshit style seems much better suited to her usual real-world sociopolitical/historical subjects than anything aesthetic (this is, perhaps, why I rather prefer most of her nonfiction to most of her fiction). It is true that, partly because of its author's extremely overripe, excess-seeking sensibility and partly because all of the fine European actors involved are forced to speak stilted English on a dialogue track which, as with all classic Italian films, is dubbed, The Damned frequently lands headfirst in the garish. But what a beautiful mess; because the two films share Dirk Bogarde as the star and involve the surreal lives of those accidentally embroiled on the periphery of the Holocaust, it begs a comparison to Liliana Cavani's The Night Porter. The story (a Dynasty-style series of sexual and financial coups amongst the wealthy and corrupt) and highly flourished acting are secondary, subsumed by the Visconti Aesthetic. Each visual is meant to capture something and elevate the film's stifling mood of decadence collapsing into despondency. The mood of the viewer also comes into play: If you watch the film on a carefree Sunday morning with your Starbucks in one hand, you'll be much better able to appreciate it for its singular pleasures than if you were to watch it on a more hectic weekday, when its unavoidably over-the-top, empty Eurotrash/Obsession-ad qualities are sure to appear more pronounced. Still, the film has capital-P Pageantry to spare and is exemplary on that count, if nothing else.

-Ingmar Bergman's The Serpent's Egg is, though one of the lower rungs on the very tall Bergman ladder, a much less qualified success. It's tempting to say that the film's main drawback is that it is, like The Damned, a big Continental production (produced by Dino De Laurentis, hardly a match in temperament for Bergman) in which all the European actors speak English. But oddly, it's star David Carradine's English that seems most stilted; costar Liv Ullman amply proves that she's amazing in any language. The film is on a scale a little too large for Bergman's sensibility to imprint itself on, but most of it does work.

The film's chronology ends parallel to the very seed of Hitler's National Socialist Germany. Well before Hitler's rise, according to what the film shows us, unbelievably inhumane, quasi-genocidal, Nazi-style human experiments performed by Aryan-supremacist scientists were already well underway, with ideologies waiting for a Hitler to hatch it and set it loose on the world.

Carradine plays a lost soul, an alcoholic, out-of-work circus performer whose brother has just committed suicide and whose life in Germany is a long, depressing drift (a course shared by the country, the economic depression of which eventually gave the strong-talking Hitler his in). He joins up with his sister-in-law (Ullmann), a cabaret performer/prostitute who eventually finds them both jobs at a German medical institution with some horrible secrets.

Bergman has more control than a Visconti, which renders the film much more consistent than The Damned. Bergman also knows from graceful composition and blocking; some of the scenes in The Serpent's Egg are as beautiful as anything he's ever done. And he saves the best for last: The film's ending is very fine, very skillful filmmaking that would easily fit right alongside those superb American paranoia-thrillers from earlier in the same decade (The Serpent's Egg was released in 1977); it would make a great triple-bill with Pakula's The Parallax View and Coppola's The Conversation.

24.5.04

My first screening of the Seattle International Film Festival was Lars von Trier and Jorgen Leth’s collaborative/confrontational experiment, The Five Obstructions. Von Trier evidently worships Leth’s 1967 short, The Perfect Human, and in a perverse move (the word “perversion” is thrown around a lot between the two directors, all of it relating to von Trier’s purposely impossible demands of Leth), von Trier has challenged Leth to remake the film a number of times, with each version tailored to his impossible set of demands (the “obstructions” of the title). Von Trier’s goal: To drag his idol down, to see if there’s anything he can’t do. Leth’s goal: To overcome those obstructions and make each successive copy interesting, whole, and worthwhile.

The film consists of bits of the original interspersed with documentary footage of the two directors in conversation and, of course, the newly done shorts. Von Trier’s obstructions range from the mean (one version is allowed no edit longer than 12 frames) to the socially conscious (he sends Leth to the world’s most miserable location, and makes Leth choose it himself- it turns out to be a Calcutta red-light district- and just see if he can shoot his little movie without acknowledging the teeming, impoverished surroundings) to the seemingly impossible (one version must be animated, which leads the two to argue about which of them loathes cartoons more). The final obstruction is something of a surprise, but suffice to say that the whole affair turns out to be a sort of warped love letter (could there be any other kind, considering the source?) from von Trier to Leth.

The film brought to my mind My Best Fiend, a documentary about the extremely tumultuous relationship between two Europeans even more crazy and obstinate than von Trier: German director Werner Herzog and his famously nutty recurrent collaborator, actor Klaus Kinski. We’re heavily exposed to the funny but slightly horrifying personalities of von Trier and Leth, who are both extremely intelligent, extremely creative, very opinionated, and slightly psychotic. Von Trier is something of a film-culture celebrity and (in)famous for being difficult, so it’s fascinating to see him joke with Leth, palling around and sharing witty banter and jokes while simultaneously subjecting him to a frustrating series of trials that cut straight to the heart of their creative vocation.

My only complaint: We never actually get to see the original version from 1967 in its entirety, which would seem to be a prerequisite for something like this.

On my SIFF ballot, I gave it a 4 out of a possible 5.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]