25.5.04

"YOU'RE A WASTED FACE, YOU'RE A SAD-EYED LIE, YOU'RE A HOLOCAUST"

My varied and surprisingly extensive recent home viewing has included two out-of-the-way Holocaust-themed English-language dramas from famed European directors:

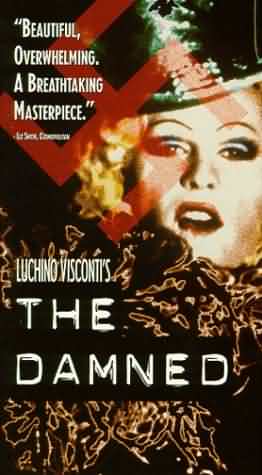

-Luchino Visconti's The Damned. I've never seen a Visconti film before, and it seems doubtful that this is the one to start with (the prime candidate for that being The Leopard, which is very shortly to be released on DVD by Criterion), but his reputation precedes him: It's all visual engorgement, content be damned (pun intended). In "I Can't Get That Monster Out of My Mind," one of her very few essays on the cinema, the notoriously hard-nosed Joan Didion very unfavorably compared Visconti to his countryman Antonioni (who makes "beautiful, intelligent, intricately and subtly built pictures, the power of which lies entirely in their structure"): "Visconti... has less sense of form than anyone now directing. One might as well have viewed a series of stills, in no perceptible order, as his The Leopard."

Now, I consider Didion a first-rate writer, but her relentless, absolutely-no-bullshit style seems much better suited to her usual real-world sociopolitical/historical subjects than anything aesthetic (this is, perhaps, why I rather prefer most of her nonfiction to most of her fiction). It is true that, partly because of its author's extremely overripe, excess-seeking sensibility and partly because all of the fine European actors involved are forced to speak stilted English on a dialogue track which, as with all classic Italian films, is dubbed, The Damned frequently lands headfirst in the garish. But what a beautiful mess; because the two films share Dirk Bogarde as the star and involve the surreal lives of those accidentally embroiled on the periphery of the Holocaust, it begs a comparison to Liliana Cavani's The Night Porter. The story (a Dynasty-style series of sexual and financial coups amongst the wealthy and corrupt) and highly flourished acting are secondary, subsumed by the Visconti Aesthetic. Each visual is meant to capture something and elevate the film's stifling mood of decadence collapsing into despondency. The mood of the viewer also comes into play: If you watch the film on a carefree Sunday morning with your Starbucks in one hand, you'll be much better able to appreciate it for its singular pleasures than if you were to watch it on a more hectic weekday, when its unavoidably over-the-top, empty Eurotrash/Obsession-ad qualities are sure to appear more pronounced. Still, the film has capital-P Pageantry to spare and is exemplary on that count, if nothing else.

-Ingmar Bergman's The Serpent's Egg is, though one of the lower rungs on the very tall Bergman ladder, a much less qualified success. It's tempting to say that the film's main drawback is that it is, like The Damned, a big Continental production (produced by Dino De Laurentis, hardly a match in temperament for Bergman) in which all the European actors speak English. But oddly, it's star David Carradine's English that seems most stilted; costar Liv Ullman amply proves that she's amazing in any language. The film is on a scale a little too large for Bergman's sensibility to imprint itself on, but most of it does work.

The film's chronology ends parallel to the very seed of Hitler's National Socialist Germany. Well before Hitler's rise, according to what the film shows us, unbelievably inhumane, quasi-genocidal, Nazi-style human experiments performed by Aryan-supremacist scientists were already well underway, with ideologies waiting for a Hitler to hatch it and set it loose on the world.

Carradine plays a lost soul, an alcoholic, out-of-work circus performer whose brother has just committed suicide and whose life in Germany is a long, depressing drift (a course shared by the country, the economic depression of which eventually gave the strong-talking Hitler his in). He joins up with his sister-in-law (Ullmann), a cabaret performer/prostitute who eventually finds them both jobs at a German medical institution with some horrible secrets.

Bergman has more control than a Visconti, which renders the film much more consistent than The Damned. Bergman also knows from graceful composition and blocking; some of the scenes in The Serpent's Egg are as beautiful as anything he's ever done. And he saves the best for last: The film's ending is very fine, very skillful filmmaking that would easily fit right alongside those superb American paranoia-thrillers from earlier in the same decade (The Serpent's Egg was released in 1977); it would make a great triple-bill with Pakula's The Parallax View and Coppola's The Conversation.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]